With less than one hundred people speaking the Wolastoqiyik language, Jeremy Dutcher understands the call and plea to honour, remember, and learn Indigenous languages.

The Canadian Government’s Indian Act and the forces of assimilation were designed to eradicate traditional Indigenous social, cultural, and political practices across Canada, such that much of the Wolastoq people’s language and culture were lost, as it was illegal to even sing their songs.

Rediscovering Wolastoqiyik Songs

Jeremy Dutcher was born in New Brunswick in 1990 and is member of the Tobique First Nation, situated along the Saint John River. He attended Dalhousie University in Halifax to study classical music and branched out to take courses in social anthropology. During his studies, he became interested in exploring the tonal differences between western classical music and the traditional music of his people, the Wolastoqiyik.

Jeremy’s life path changed in 2013 during one of his many conversations with Maggie Paul, an elder, teacher, and song carrier who has spent most of her life trying to sustain Wolastoqiyik musical traditions.

[Paul] knew I was interested in our traditional music and told me, ‘If you really want to know about the old songs, you need to go the museum—that’s where they’re kept.’

—Jeremy Dutcher

Paul encouraged him to go explore these Indigenous recordings and bring them back to where they belong, back to the community.

If you lose the language, you’re not just losing words; you’re losing an entire way of seeing and experiencing the world from a distinctly indigenous perspective.

— Jeremy Dutcher

Reclaiming Language

Jeremy received funding from the Canada Council of the Arts to travel to the Canadian Museum of History in Gatineau, Quebec, and explore the ethnographic archives of William Mechling, an anthropologist who studied the Wolastoqiyik First Nations communities, living there from 1904 to 1911, and collecting 100 songs and documenting stories about their community. This colonial idea of documenting what they believed to be a dying culture was quite common at this time.

Mechling created some of the “the earliest known recordings of Indigenous people” from over a hundred years ago preserved on wax cylinders. Using his classical music training, Jeremy listened and transcribed songs he had never heard before sung by his ancestors. He would sing along with them, first in unison and then in harmony.

Watch: Artist in Residence

As a 2016 Artist in Residence at the National Music Centre in Calgary, Alberta, Jeremy Dutcher worked to incorporated William Mechling’s wax cylinder recordings from Wolastoqiyik (Maliseet) communities into his music, fusing elements of classical, contemporary, traditional, and jazz music. Learn how he sees his work as a reclamation of the music of his people and an expression of the community's endurance.

Watch Jeremy Dutcher’s Artist in Residence video at the National Music Centre. In the video, he describes his experience in these archives, and his decision to create his debut album Wolastoqiyik Lintuwakonawa, an album sung entirely in the Wolastoqiyik language. The title translates to "The Songs of the People of the Beautiful River."

This online exhibition uses third-party applications including Spotify and YouTube. Check with your organization’s web administrator if you are unable to access content from these channels in the exhibition.

Courtesy of the National Music Centre. Please note: This third party video does not provide closed captions.

View Transcript[Jeremy Dutcher] I'm really excited to bring this project to the National Music Center as well because you know I think indigenous music has been really underrepresented in what people think of this Canadian music. Right? You know this is this is the music of this land you know and so to be able to sing these songs in a space like this and so really in a way like reclaim it and say like we're still here this is our this is our music and this has been our music for generations and and now we get to share it with you.

We're finally at a place now culturally where that is a conversation that can be had.

[Music]

[Jeremy Dutcher] The source material for this project is wax cylinder recordings done in the early 1900s by this anthropologist named William Mechelen. William Mechelen, he went into our communities in the East Coast and lived there for about seven years. So he collected over a hundred of our traditional chant songs on wax cylinder recordings. Something sort of similar to this. So this is very very early recording technology. Before there were records before any of that right we were recording on wax cylinders.

[Music]

[Jeremy Dutcher] I get to sing with my ancestors with these wax recordings but also it's about looking forward and moving forward. The kinds of music that I do and that I love throughout my life you know are you know jazz music and opera music and traditional chant music and these are genres that aren't often speaking to each other. I sort of see it as my role to sort of turn them in you know on each other and to have this conversation between genres that don't really on the surface of it fit together.

[Music]

[Jeremy Dutcher] I came to find out that actually there was a great sense of improvisation with Indigenous music on the East Coast back in the day. Right? Which is not the case today. Singers would add their own flares and go off on tangents and have these massive improvisations. So I really wanted to explore that element of it as well. I hope that it spurs other other young people to think about lineage and history in the music that they make today.

[Music]

More Than a Call and Response

When listening to Jeremy’s music, you initially hear a tenor melody accompanied by a solo piano. As the songs and momentum build to their climaxes, many different musical influences come together weaving opera, jazz, and traditional chanting songs together.

Highlighted throughout, scratchily sounding snippets of voices are heard from the original wax recordings, as Jeremy’s ancestors begin to sing with him.

Jeremy embodied his contemporary musical understanding, just as his ancestors would have, taking and singing the melodies in various ways and then bringing them back together again. These influences allow him to have a conversation across generations through time and space.

Listen: Ultestakon

To be able to sit down and hear what my ancestors were singing and thinking about and just what their world was all about, that was a really special thing.— Jeremy Dutcher, Interview with the National Music Centre, 2016

This online exhibition uses third-party applications including Spotify and YouTube. Check with your organization’s web administrator if you are unable to access content from these channels in the exhibition.

Recognition & Awards

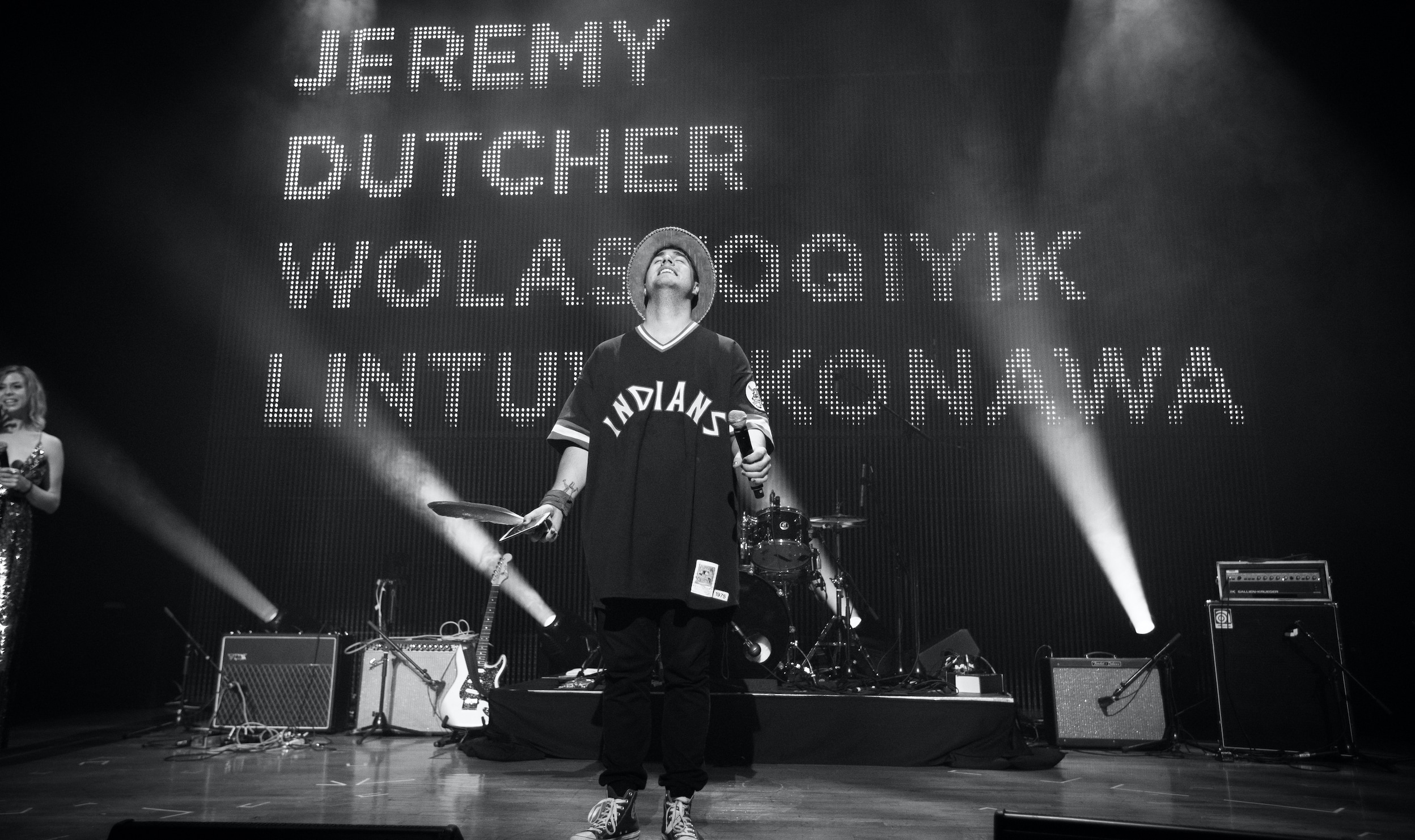

Independently releasing his album, Wolastoqiyik Lintuwakonawa, Jeremy won the 2018 Polaris Music Prize and took the music world by storm.

In 2019, Jeremy won the JUNO Award for Best Indigenous Album, a category which was subsequently retitled to Indigenous Artist or Group of the Year Award in 2020 as a step towards inclusivity.

Jeremy continues to use his musical platform and voice as a space for conversation and for activism calling Canadians to move forward in a positive way.

I am not the Indian you wanted, but I am the Indian you need.

—Jeremy Dutcher, Interview with The Guardian, 2019

Jeremy Dutcher at the 2018 Polaris Music Gala following his win for his album "Wolastoqiyik Lintuwakonawa."

Photo by Dustin Rabin

This is what holding space looks like. Reconciliation is a lofty goal. It is a dream. It does not happen in a year. It takes time. It takes stories. It takes shared experience. It takes music. I have hope. I have to.

— Jeremy Dutcher, 2019 JUNO Awards

Our Music is Saying Something

Jeremy commends the work of artists such as Buffy Sainte-Marie, an artist he has listened to and looked up all of his life but says that indigenous music does not need to be separated from other genres:

Because our music is not niche. Our music is saying something.

—Jeremy Dutcher

His album is not only about linguistic revival, but also touches on continued important Indigenous issues, such as the lack of clean water and missing and murdered Indigenous women.

A Table of Indigenous Excellence

The first track off Jeremy Dutcher's 2018 album Wolastoqiyik Lintuwakonawa is "Lintuwakon ‘ciw Mehcinut", which means "Death Chant" in the Wolastoqiyik language. The track fuses Dutcher's original music with a recording made over 100 years ago of Wolastoqiyik ancestor Jim Paul discussing the topic of death and the afterlife.

To record the music video for “Mehcinut”, Dutcher brought together 15 Indigenous artists, leaders, and activists across various disciplines to the Aga Khan Museum in Toronto in 2019. As you watch the music video below, look for prominent Indigeous artists Bear Witness from A Tribe Called Red and Lido Pimienta at the opposite ends of what Dutcher calls a “Table of Indigenous Excellence."

[The music video was] my opportunity to highlight some bright lights within indigenous artistic communities from coast to coast to coast — artists who are making an impact and dreaming us into a resplendent, new future. Diverse representations of who we are as indigenous peoples are critically important in this moment.

—Jeremy Dutcher

Watch: Mehcinut

This online exhibition uses third-party applications including Spotify and YouTube. Check with your organization’s web administrator if you are unable to access content from these channels in the exhibition.

Courtesy of Jeremy Dutcher. Please note: This third party video does not provide closed captions.

View Transcript[Jeremy Dutcher enters an empty concert hall. He is wearing a long translucent cape on top of his red shirt and red pants. He has a brown top hat that is decorated with a feather. He moves through the room while lightly waving his cape. He sits down next to a piano in the centre of the stage. He begins playing on the piano. He is singing a song titled "Mehcinut". Dancers appear on the stage behind Jeremy Dutcher. The dancers' hairstyles and clothes are inspired by traditional Indigenous clothes. The dancers perform a dance inspired by traditional Indigenous dances. An elderly Indigenous woman dressed in red appears on screen briefly. She is surrounded by a falcon and a young woman. The dancers on stage slow down their movements. A purple and elaborately geometrical ceiling appears on screen. Indigenous dancers briefly reappear before the ceiling fills the screen again. The image of the ceiling fades into the image of a circular staircase. Jeremy Dutcher runs down on the staircase with his cape wide open. The image of the staircase fades into an image of the inside of a gramophone. The gramophone is placed on a long table. It is nighttime and the moon fills the sky. The table is surrounded by colorfully dressed men and women. The table is set for a dinner and is full of food such as a stuffed turkey; a sea lion and a warthog's head. The woman in red is raised in her chair by three young people. She is in the concert hall where Jeremy Dutcher performs the song. The woman in red and other people on stage make a slight bow toward Jeremy Dutcher. The woman in red joins the dancers in their performance and interacts with Jeremy Dutcher. People sitting at the long table briefly reappear on screen. The woman in red is sitting at the table and she is smiling. Jeremy Dutcher left the piano. He is spinning while a woman holds his head in her hands. A young woman holding an infant child appears on screen. They are outside at night and the moon fills the sky in the background. She hands the child to the woman in red. At dawn, Jeremy Dutcher walks outside of a modern building next to a large pool. He opens his cape. The screen fades to black. A passage written in Wolastoqiyik language appears on screen followed by an English translation. Credits.]

I believe my work is to engage the young people and get them excited about the wealth of knowledge that sits within our language and our songs. The days of internalised colonialism are done.

— Jeremy Dutcher, The Guardian, 2019

Building on Future Generations

Jeremy continues to work with younger generations to help them find their voice in music. He expresses and intersects his two-spirited identity with his Indigeneity and cultural expression, remaining fierce and unapologetic for himself and his music.

Dive Deeper

Official Web Site of Jeremy Dutcher

Bernard C. Perley. Defying Maliseet Language Death: Emergent Vitalities of Language, Culture, and Identity in Eastern Canada. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011.